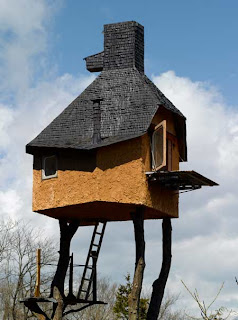

Takasugi-an by Terunobu Fujimori

La casa de té, de Terunobu Fujimori, se encuentra en la ciudad de Chino, Nagano, Japón.

La casa de té se construye encima de dos castaños, cortados de una montaña cercana y transportado al sitio, y sólo es accesible por escaleras autónomas apoyadss contra uno de los árboles.

Siguiendo la tradición de los maestros de té, que mantiene el control total de la construcción de sus casas de té, Fujimori diseñó y construyó la estructura para su propio uso. El interior está cubierto de yeso y esteras de bambú. El nombre Takasugi-un significa: "una casa de té [construido] demasiado alto." A continuación un texto acerca de la Casa de Té, escrito por el autor de la misma: El arquitecto y académico, Terunobu Fujimori, ha observado que un teahouse es “the ultimate personal architecture.†Su compacidad extrema, que como máximopuede acomodar cuatro y medio tatami (2,7 metros cuadrados), o incluso sólo dos tatamis (1,8 plaza metros) de espacio, lo hace sentir como si fuera una extensión del cuerpo, "como una pieza de ropa." Los maestros del té tradicionalmente mantienen el control total de la construcción de estas "cajas", cuya sencillez es su principal preocupación. Por lo tanto, prefiere no involucrar a un arquitecto o un experto carpintero - un acto considerado como demasiado ostentoso. A raÃz de esta tradición, Fujimori decidió construir una humilde teahouse para sà mismo y por sà mismo en un pedazo de tierra que pertenecÃa a su familia. Su interés como arquitecto, sin embargo, más en empujar los lÃmites y las limitaciones de la tradicional teahouse en lugar de buscar el arte de hacer el té, y como resultado, ha creado una pieza muy expresiva de arquitectura. Takasugi-un, que significa literalmente, "una casa de té [construida] demasiado alto," es como un árbol más que una casa de té. A fin de llegar a la habitación, los huéspedes deben subir las escaleras independientes apoyados contra una de las dos castaños en los que apoya a toda la estructura. Los árboles fueron cortados y llevados en los alrededores de la montaña en el sitio Se quitan los zapatos a mitad de camino. Una vez dentro de la habitación, que simplemente se rellena con yeso y alfombras de bambú, el arquitecto del espÃritu aventurero da paso a la serenidad más adecuada para el propósito de hacer té y calmar la mente. La sala muestra una gran ventana que enmarca los ojos del pájaro perfecto punto de vista de la ciudad donde creció Fujimori. Sustituye eficazmente kakejiku (una imagen de desplazamiento), que indican pistas adecuadas a la época del año en teahouses tradicionales. Este kakejiku no sólo muestra los cambios estacionales, el ciclo, sino también los profundos cambios irreversibles que tienen lugar en ciudades de provincia como Chino. También visible, a la distancia está primer proyecto de Fujimori, Moriya Jinchokan Museo Histórico. El arquitecto aficionado por lo personal, lo vernáculo, y cada dÃa es particularmente evidente en esta casa de té.![View in fullscreen [Press F11] Fullscreen](http://btemplates.googlepages.com/fullscreen.gif)

Takasugi-an by Terunobu Fujimori Following yesterday’s Charcoal House story, here’s another of Terunobu Fujimori’s projects photographed by Edmund Sumner: this time Takasugi-an, a tea house in Chino, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. The tea house is built atop two chestnut trees, cut from a nearby mountain and transported to the site, and is accessible only by free-standing ladders propped against one of the trees. Following the tradition of tea masters, who maintained total control over the construction of their tea houses, Fujimori designed and built the structure for his own use. The interior is covered with plaster and bamboo mats. The name Takasugi-an means, “a tea house [built] too high.†The academician and architect, Terunobu Fujimori, has observed that a teahouse is “the ultimate personal architecture.†Its extreme compactness, which would at most accommodate four and a half tatami mats (2.7 square metres) or even just two tatami mats (1.8 square metres) of floor space, makes it feel as though it were an extension of one’s body, “like a piece of clothing.†The tea masters traditionally maintained total control over the construction of these “enclosures,†whose simplicity was their main concern. They therefore preferred not to involve an architect or even a skilled carpenter - an act considered as being too ostentatious. Following this tradition, Fujimori decided to build a humble teahouse for himself and by himself over a patch of land that belonged to his family. His interest as an architect, however, lay more in pushing the limit and constraints of a traditional teahouse rather than pursuing the art of tea making, and as a result, he has created a highly expressive piece of architecture. Takasugi-an, which literally means, “a teahouse [built] too high,†is indeed more like a tree house than a teahouse. In order to reach the room, the guests must climb up the freestanding ladders propped up against one of the two chestnut trees supporting the whole structure. The trees were cut and brought in from the nearby mountain to the site. Shoes are taken off at the midway point. Once inside the room, which is padded simply with plaster and bamboo mats, the architect’s adventurous spirit gives way to the serenity more suited to the purpose of making tea and calming one’s mind. The room displays a large window that frames the perfect bird’s eyes’ view of the town where Fujimori grew up. It effectively replaces kakejiku (a picture scroll) that would indicate clues appropriate to the time of the year in traditional teahouses. This kakejiku not only displays the cyclical seasonal changes but also the profound irreversible changes taking place in provincial towns like Chino. Also visible in the distance is Fujimori’s very first project, Jinchokan Moriya Historical Museum. The architect’s penchant for the personal, vernacular, and everyday is particularly evident here in this swaying teahouse.